|

| Photo by Dieder Plu |

Lawyers are natural pack rats, and document management systems, coupled with cheap data storage, are their enablers. But is the hoarder lifestyle good for lawyers?

For decades lawyers have served as “free warehouses” for their

clients’ files. As a result, a lawyer’s

heirs may discover that all they have inherited is a mountain of paper, the mass

of which evokes the final scene from Raiders

of the Lost Ark. This mountain now has

a digital layer which is just as, if not more, challenging to scale.

|

| This amazing matte painting by Michael Pangrazio took 3 months to create |

Genesis of the Problem

Colo. RPC 1.16(d) commands: “Upon termination of

representation, a lawyer shall . . . surrender[]

papers . . . to which the client is entitled.”

Few lawyers do, and few clients complain. Why?

To a lawyer, retention of a client’s file is security that it

will return for future services. Moreover,

file pruning and delivery is a time-consuming, non-billable task. As long as warehouse space is cheap, it’s

easier and potentially more profitable for a lawyer to kick the can down the

road, even all the way to the graveyard.

For their part, most clients are delighted to have their lawyer retain

their files, especially if they are voluminous, since it is virtually unheard

of for a lawyer to charge for this perpetual maintenance. With no incentive for either lawyer or client

to houseclean, why bother?

One consequence of this mutual neglect is the rise of

“Inventory Counsel,” an entire group within the Office of Attorney Regulation Counsel tasked with overseeing the disposition of files when an attorney dies

or becomes incapacitated without having made arrangements for the handling of his

practice. More than 21,000 of the 48,000

attorneys registered in Colorado are baby boomers who have, or will, stop

practicing – one way or another – within the next two decades. Little wonder that in 2014 OARC inventoried

4,301 client files, a 44 percent increase over 2013 – just the tip of a rapidly

aging iceberg.

The rise of e-mail and electronic documents has exacerbated

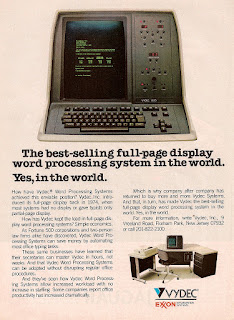

the problem. Vydec & Wang is not the

name of an immigration law firm. Together

with NBI, Linolex, and Lexitron, these were the earliest dedicated word processing

systems, each with its own proprietary software. All were long ago consigned to the Museum of

Computer Antiquities, along with 5-1/4” and 3-1/2” floppy discs. How many attorneys maintain the obsolete

software and hardware required to read the native files created by these

systems?

The rise of e-mail and electronic documents has exacerbated

the problem. Vydec & Wang is not the

name of an immigration law firm. Together

with NBI, Linolex, and Lexitron, these were the earliest dedicated word processing

systems, each with its own proprietary software. All were long ago consigned to the Museum of

Computer Antiquities, along with 5-1/4” and 3-1/2” floppy discs. How many attorneys maintain the obsolete

software and hardware required to read the native files created by these

systems?

Even if an attorney has faithfully converted all of her electronic files through each successive iteration of technology, the magnitude of the Mount Megabyte, and the imperative to better manage it, will hit home the first time a client with hundreds of digital files requests them, or an e-discovery request is served. For law firms, the problem is magnified by the number of time-keepers who have worked on a matter. Woe unto the lawyer or firm who has not implemented and scrupulously followed a document management plan when the litigation-hold letter arrives.

Solutions and Strategies

Adopt a File Retention Policy (and

Follow It!)

A partial solution is offered by Colo. RPC 1.16A (Client

File Retention), perhaps the single most important ethics rule enacted in the last

decade. Rule 1.16A provides four methods

of turning a document mountain into a more manageable mole hill:

The first and easiest solution is to simply “surrender” the

file to the client. This can be done

either by delivering the file or notifying the client it is available for

pick-up. Be sure to get and keep a

signed receipt which should expressly inventory important documents. Also, if circumstances warrant, Bates

numbering and copying each page will avoid later disputes as to what was in, and

what was not in, a file. The cost of continued

storage in such cases is more than compensated by the peace of mind provided,

and can be lessened by digitizing the retained file.

Second, a client may give written consent to destroy its

file, provided there are no pending or threatened legal proceedings known to

the lawyer that relate to the matter.

Third, a lawyer may give notice to a client of his intent to

destroy a closed file so long as notice is provided at least 30 days before the

declared destruction date. Rule 1.16A

(d) explicitly allows:

A lawyer [to] satisfy the [30-day] notice

requirement[] . . . by establishing a

written file retention policy consistent with this Rule and by providing a notice of the file retention policy to the client in a fee

agreement . . . .

The fourth and most powerful file clean-up tool is provided by

Rule 1.16A (2)(b):

At any time following the expiration of a period of ten years following the termination of

the representation in a matter, a lawyer may destroy a client's files

respecting the matter without notice to

the client, provided there are no pending or threatened legal proceedings

known to the lawyer that relate to the matter and the lawyer has not agreed to

the contrary.

This provision enormously lessens the burden of providing

notice, and is the only practical solution when a client has disappeared. An attorney who avails himself to any of

these methods should always review, remove, and retain original documents, such

as deeds, wills, notes, and stock certificates.

Deploy a Document Management System

Implementing a document management system (DMS) is essential

to herding digital cats. For a solo

practitioner a simple folder-tree system, hierarchically organized by client,

matter, and document type, may be sufficient.

For larger firms, bona

fide DMS software is essential, as is insisting on attorney

compliance. If “garbage in, garbage out”

is bad, nothing in is infinitely worse.

While some gap between client intake and the creation of a client DMS

profile is inevitable, attorneys must be constantly nagged reminded to

move locally-stored documents to the DMS if the additional overhead of searching

and retrieving documents from every time-keepers’ PC is to be avoided. Doing this, and limiting users’ ability to

delete documents from the DMS, will lessen the havoc created when a hoarding

attorney bolts a firm and wipes his hard drive clean.

Malpractice Considerations

The virtues of implementing and following a document

management system commend themselves.

There is, however, a philosophical divide on the question of whether

retaining documents – especially e‑mail – for longer than is required helps or

hurts an attorney when sued for malpractice.

One camp espouses “if it doesn’t exist, it can’t be

discovered.” Another camp believes that

if a matter has been conscientiously and competently handled, retained files,

especially electronic files, are more helpful than harmful in establishing that

the standard of care has been met, and in refreshing recollections. Whichever view prevails it is a question that

needs to be resolved at a policy level, since any inconsistency in file

handling is bound to be discovered and exploited by plaintiff’s counsel, even

if spoliation of evidence has not occurred.

An abridged version of

this blog originally appeared in the 14 March 2016 edition Law Week Colorado.